|

| Santos=Dumont flying over the Globe Céleste de l'Exposition Universelle de 1900 en Paris with his dirigible Number Four |

The Santos=Dumont

dream of fly over the main cities started back in 1900, when he flew over

l'exposition universelle with his

dirigible number four. Nobody depicted the adventure of flying over the biggest

cities of the world, such as New York, as Livingstone Cooper of the American

edition of Metropolitan Magazine.

Leia este artigo em Português

Leia este artigo em Português

Take a trip on a

modern concept of steampunk flight of Santos=Dumont over NEW YORK as told at

the verge of his visit to US in March 1902.

An Aerial Journey above the Sky-Scrapers, with St. Paul’s Spire as a Turning-Stake, and a

bird’s-eye view of Brooklyn Bridge.

By LIVINGSTON COOPER.

This summer will

witness in New York the realization of what makers of wonder-pictures long ago

began to create from the figments of imagination, making the upper air as

highway for travel. What Paris has seen we will behold, and the man who steered

his airship around the Eiffel Tower will make the spire of St. Paul’s Church

the turning point in an aerial voyage covering the length and breadth of

Manhattan Island. He will sail in among the sky scrapers which environ the

historic edifice, steering clear of them, after rounding his mark, will retrace

his course to the point of starting.

|

| Santos=Dumont consulting time in his brand new Cartier |

When Santos=Dumont

rises into the air somewhere in the upper portion of the city, millions of New

Yorkers will wish him bon voyage, and millions of faces will turn upward to

watch his flight. The shrieks of steam whistles will greet him all along the

way, while windows and housetops will flutter in his sight like masses of

waving handkerchiefs and flags.

New York will not

regret the exhibition as a wonder, but simply as a novelty. It will be a thing

long expected because long promised. The wonder is that the promise involved in

the first balloon, sent into the air of the eightieth century, remains only partially

fulfilled in these opening years of the twentieth century. New York will accept

the aeroyacht, when it comes in its perfection, just as she has accepted the

automobile, dissipating is novelty by making it as familiar as many other

things are which would have sent our great-grandfathers to their knees in

prayer for protection against the power of Beelzebub. We would not try to get

along without any one of those once wonderful things to-day; we are reaching

after more in the same line. Santos=Dumont will bring to us only a hint, after

all, though a very promising on, of another convenience of which we have been

dreaming, for which we are determined to posses some day. Behind the enthusiasm

attending his exhibitions there will be not more of exultation over his

achievement than of quickened hope for the speedy solution of the problem

involving the air with the freedom and swiftness of the birds.

Santos=Dumont will

sail his airship under and over Brooklyn Bridge. The daring Brazilian is but a

young man, not yet thirty years old, but he was a boy who could be trusted at

the throttle of one of the locomotives used upon his father’s vast coffee

plantation just about the time when that mighty span over the East River, the

wonder of its highway of a multitudinous traffic. It is no longer a wonder to

the New Yorker, who will stand with many thousands upon its broad promenades

and great platforms, watching the aeronaut in his flight. Their gaze will

follow him as he flats above that other colossus standing astride the stream

further up, but there will be no realization of the fact that two new wonders

are included in the view – both only promises of what is to be. They know that

ere long they will walk and ride across the newer, bigger bridge, but their one

ambition, as they behold the scene, will be some day to soar above it. And when

that some day comes – but why anticipate the decadence of wonder into that

commonplace interest which will attach to the size, beauty, and speed of this

or that millionaire’s aerial flyer?

One of the journeys

which will probably be undertaken by Santos=Dumont will be a trip over the

harbor and bay. It would be full of interest in many ways, and the flight of

the air-ship to and around the Statue of the liberty, or down through the Narrows

and back, would be a strange contrast that the novel craft would present to the

fleet of steam vessels which would keep pace with it on the waters of harbor

and bay.

Unfortunately, that flight over New York, with Dumont piloting it, never happened. However, Edward Boyce did so with a Dumont aircraft - Airship No. 6 was the first to fly in America.

From the shores it

would appear like a giant bird hovering in air above the fleet. Still more

exciting would the exhibition become should the aeronaut put on speed and try

conclusions with some of the swift steam yachts or big passenger boats. The

air-ship and one of the palatial boats that ply between New York and the

Atlantic Highlands could make a very pretty race. It would be worth going miles

to see. A trip up and down the Hudson would be another exhibition whereby

Santos=Dumont might display the abilities of his craft. The airship flying

along abreast the precipitous walls of the Palisades would be a scene almost

weirdly picturesque.

Whatever trips may be

decide upon by the aeronaut during his stay in New York, none will be more

interested than those which will be made over the city itself. They will not be

lacking in the element of excitement, for the tall buildings which loom up,

singly and in groups, in various sections of New York and Brooklyn, would serve

as turning marks for a great variety of courses. These could be laid out with a

view to testing the dirigibility of the airship in any possible direction on a

single trip, affording definite indications of the degree of control possible

under any given conditions. With triangular, four sided, and zigzag courses,

accurately marked, the performances of the airship could be made extremely

valuable, and the possibilities which exist in this direction are of vast

importance if aerial voyaging is to become, even for pleasure purposes, the

practical thing that the world is looking for. The airship may be developed

much beyond what Santos=Dumont has made it, and still be only a plaything for

the most venturesome. But it will not fulfill its mission until, like the

automobile, it is developed into some form where it will serve useful purposes.

This is a more serious

view of the matter, however, than will be taken by the multitude whose eyes

will follow Santos=Dumont in his venturesome journeys, whose voices will rise

in boisterous greeting form every point where people will mass themselves to

watch him. They will be trilled by excitement when his docile leviathan of the

air swoops down from the clear heights to pick its way among towering

structures and sweeps around some designated mark. He will approach disaster

none too closely to minister to their appetite for sensation. His avoidance of

it will be the glory of the moment. The full glory of its significance will

come with the later sober reflection upon what it will mean for mankind in that

constantly accelerating march of progress which scorns limitations.

Unfortunately, that flight over New York, with Dumont piloting it, never happened. However, Edward Boyce did so with a Dumont aircraft - Airship No. 6 was the first to fly in America.

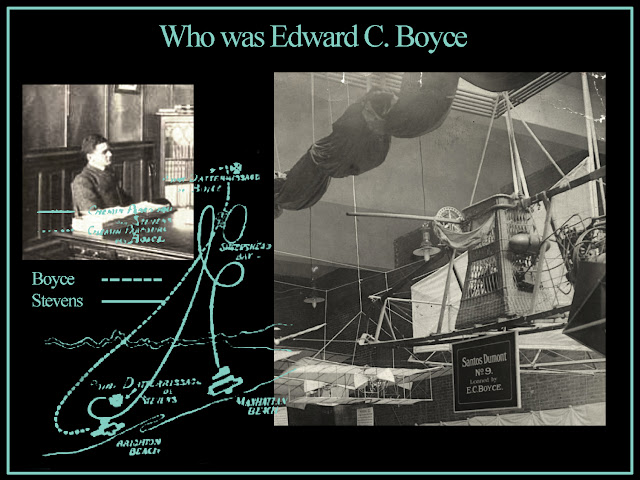

But after all, who was Edward?

Edward C Boyce known for having bought La Baladeuse Nº9 and Santos=Dumont Nº 8, was the first man to pilot an airship in America. He was also an accomplished architect, amusement park mogul and co-owner of Dreamland in Coney Island as well as the White City in Chicago.

It is important to say here that perhaps the Number 8 airship, purchased by Boyce, is the modified Number 6, just as the Number 6 came from modifications to the Number 5 after the August 8 accident. The criteria for numbering Dumont's dirigibles were never clear.

Boyce was undoubtedly a multifaceted figure in the early 20th century, who devoted himself to the emerging aviation of the time, becoming one of the pioneering founders of the Aero Club of America.

That's where the intriguing part comes – we don't have his date of birth, death, little is known about his contributions to the Aeroclube, not even a good photo of him.

|

| Photo of Boyce's office 302 Broadway, NY - Modern Amusement Parks Catalog 1904 |

One of the most intriguing claims about him is that he was the first man to fly an airship in America, as reported in THE EVENING TIMES article of October 1, 1902.

|

| Article in THE EVENING TIMES of October 1, 1902. |

“The dispute was between the airship Santos=Dumont Nº 6 (some dumontologists believe that it could have been Nº 8), the great airship that was in Brighton Beach all summer, and the Pegasus, airship of the rival aviator, that was in a stable in Manhattan”.

It is curious that Stevens' exploits have received more prominence in the historical record, while Boyce has remained relegated to a secondary role.

As for Boyce's description, the article goes on to say that “...Edward C. Boyce, a wealthy young man, who was vice president of the Syndicate Construction Company, whose offices are at 74 Broadway. He has an income of $50,000 a year, and a passion for experiments, is a member of the Aeroclube, and his fight was in fulfillment of his declaration that Santos-Dumont No.6 should fly it he had to take her up himself.”.

Huh! Why couldn't Dumont fly his own airship in America? - ...let's continue...

“...It was an important race.

...

The flight was a surprise; Boyce began without any warning, Mr. Stevens saw his companion in the air and was unwilling to allow the honor of the first airship ride in America to go to his rival, so within twenty minutes, after Mr. Boyce was in the air, he took his out of the shed in Brighton Beach and shot it up onto the roofs of houses.” Ready Mr. Stevens was also venturing over Manhattan.

The article says that Mr. Boyce landed smoothly in a field, so easily he wouldn't have broken an egg, while Stevens fell into an electric light pole and tangled himself in the wires.

Boyce's flight was a jagged ellipse from Brighton Beach in the northeast to a field in Sheepshead Bay. He circled his starting point and actually went into the wind most of the way.

This same article has been published in newspapers around the world, yet it appears that Mr. Boyce decides to disappear from history for a while.

It is important to note that Pegasus itself, which was not a replica of the number 6, shared extremely similar characteristics with Dumont's airships.

Oh, and we also know that in this beautiful Dreamland shed, number 9 was on display before it went to the Smithsonian - Thankfully, it didn't burn in the great Coney Island fire of 1911.

But the question remains: why has Edward C. Boyce's story been so overlooked in the historical record?

|

| Left, Clement nacelle and engine from La Baladeuse #9 at the Smithsonian, on loan from Edward C. Boyce - right, Leo Stevens' airship nacelle on display in the beautiful Dreamland pavilion.. |

I have a theory, which perhaps seems a bit conspiratorial – that it was because of his friendship with Santos=Dumont.

Yes, saying that Santos=Dumont's aircraft, Nº 6, (perhaps Nº 8) and Nº 9, bought by Boyce, ended up at the Smithsonian Institution, has a bad political connotation for the history told in America.

Anyway, to mention less conspiratorial reasons, here are other possible reasons:

Lack of Proper Documentation: In an age when historical documentation was not always as comprehensive or detailed, it is possible that records about Boyce were lost or not properly preserved;

Historical inequalities: Historical inequalities, such as gender, racial or social class prejudices, may have influenced the representation and protagonism of certain individuals in historical records;

|

| La Baladeuse Nº 9 de Santos=Dumont, which was purchased by Edward C. Boyce displayed in a beautiful pavilion at Dreamland in Coney Island |

Focus on other pioneers: In a competitive field like aviation and the amusement park industry, more prominent names may have received more attention, leaving figures like Boyce in obscurity.

In Search of Historical Truth.

Although the story of Edward C. Boyce remains shrouded in mystery, it is essential to continue the search for information about his life and accomplishments. Research into primary sources such as old newspapers, business documents and personal files can shed light on Boyce's legacy. Also, it's important to question the official story and pursue one.

If any readers know anything else and want to add, please comment - It will be a pleasure to know more about this great man.

The Mystery of Airships Number 6 and Number 8

Para saber se existiu ou não um dirigível número 8, a resposta pode ser encontrada nas evidências e em artigos de jornal.

De acordo com um artigo no The Sketch of London em 4 de junho de 1902, o dirigível N.6 que foi resgatado do acidente na baía de Monte Carlo, Mônaco, em 13 de fevereiro de 1902, foi danificado no Crystal Palace em Londres (provavelmente sabotado), e por lá ficou até 1919 (pelo menos a quilha e o invólucro). Renato Oliveira acredita que o cesto exposto no Le Bourget é o que foi resgatada do mar.

Por outro lado, de acordo com o The Evening Times, em outubro de 1902, o Sr. Boyce voou com ele.

Portanto, é provável que o Sr. Boyce tenha pilotado o N.8 e não o N.6, Santos=Dumont fez uma cópia do N.6 para levar para a América.

O próprio Leo Stevens tinha várias cópias de seu dirigível espalhadas pelo mundo; 2 na Inglaterra 1 nos Estados Unidos e outro na Itália idênticos de 1902 a 1905.

Renato Oliveira afirma que "cronologicamente não havia como o N.6 estar em Londres e Nova York ao mesmo tempo".

|

| The article of The Sektch of London, June 4, 1902, with the picture of the huge shed specially built to house the airship Santos=Dumont N.6, near the Crystal Palace pole, in London |

Well, let's wait, soon he will release a book on the subject.

Next, the article of

The Sektch of London, June 4, 1902

----

The threatening eye with which, according to Shakspere, Fortune looks upon men when she means most good has been almost too much in evidence with M. Santos-Dumont. Air-ship after air-ship has belied its name by sinking unbidden to the earth; on more than one occasion the daring aeronaut has been in imminent peril of his life, and now the public lights which were to have begun this week have of necessity been ostponed indefinitely. Even M. Damont's customary nonchalance must have been sorely tried when, on his return from Paris, it was found that the silken casing of his balloon had been badly left in several places. The scene of the unfortunate accident outrage, as the case may be, was the huge shed specially constructed near the Crystal Palace polo-ground. It had been deemed visable to hold some preliminary experiments before the public trials, the inventor's two French assistants were busily adjusting the chanical portion of the vessel when its owner arrived. All was apparently well then, but while he was at luncheon it was discovered that the silk was torn and quite beyond repair. Detectives and police were, of course, at once summoned to take the matter in hand. The theory was that the damage was malicious, or, at least, mischievous;

-------

read the full article of THE EVENING TIMES, 1º de outubro de 1902:

THE EVENING TIMES, October, 1st 1902

RIVAL AIRSHIPS IN EXCITING RACE THROUGH THE CLOUDS

Santos-Dumont and Stevens Machines High in the Sky Above Sheepshead Bay Interest Racegoers.

American-Built Flyer Guided by Leo Stevens Victorious Over the Brazilian Vessel. Met With Mishaps.

NEW YORK, Oct. 1-America had its first race of airships yesterday.

The contest was between SantosDumont N. 6, the big airship which the Brazilian would not go up in and put go up is and which has been at Brighton Beach all summer, and Pegasus, the rival flyer, that has been stabled at Manhattan, and which has made one or two false starts.

|

| Reception of Satnos=Dumont in the United States on April 19, 1902. Moments of joy alongside Emmanuel Aimé and Samuel Pierpont Langley |

Yesterday both navigated the air.

The Santos-Dumont was operated by Edward C. Boyce, a wealthy young man, who la vice president of the Syndicate Construction Company, the offices of which are at No. 74 Broadway. He has an income of $50,000 year, and a passion for experiments, is a member of the Aero Club, and his fight was in fulfillment of his declaration that Santos-Dumont No.6 should fly it he had to take her up himself.

Pegasus was operated by Leo Stevens, an aeronaut, and a candidate for the $200,000 prize which is to be sailed for at the St. Louis Exposition. He has made many ascensions in hot-air balloons near New york.

Both machines flew high and long and well. The Stevens airship crossed the path of the other and went much higher, but as it was a test of divisibility there is some doubt whether the higher flight counts for our against man who made it.

Was an important Race.

From the ground it seemed that the low flight machine was able to turn more easily, and to be more under control than the other, but Mr. Stevens disputes this.

The flight was a surprise; Mr. Boyce started without any announcement, and Mr. Stevens started because the other fellow did and was not going to see the honor of the first voyage of airship voyage in America go to his rival, so within twenty minutes, after Mr. Boyce’s machine bulged from the shed at Brighton Beach and shot above the house tops, Mr. Stevens was also adventuring upward from Manhattan.

Mr. Boyce came down gently in a field, so easily, he says, that he would not have cracked an eggs ball. Mr Stevens came down on a telegraph and electric light pole and got mixed up with the wires, but he was not hurt and his machine was not damaged to amount to anything.

Mr. Boyce’s flight was an irregularity wavy line from Brighton Beach northeast to a field in Sheepshead Bay. He circled his starting point, and really went against the wind most of the way.

Mr. Stevens course was a double ellipse, according to his own statement, ranging form Manhattan north and westto his landing place on the tlegraph pole at the corner of the Sheepshead Bay Road and First Street.

Nearly Broke Up Race.

Both passed almost over the race track, and they were in sight spectators, bookmakers, and jockeys, and even the horses themselves watched nothing else. It was so serious that the Jockeys had to be admonished in the fourth race to mind their start instead of the two big cigars that bung in the air above.

It was 3:45 when Mr. Boyce made his start. He had come down to the Aerodome, which is what they call the barn in which an airship is kept, to his automobile with his wife and two little children. His little boy bewalled the fact that be could not accompany his father, and Mr. Boyce gave the word to let go, calling back directions to his party to meet him in Grimes Fields at Sheepshead Bay.

|

| Santos=Dumont reception in St Louis |

The two ropes at the rear of the airships holding it, should have them pulled off when it ascended. But one of them was not pulled by the man that held it. It went up with the balloon and was caught in by the propeller. Those on earth who saw him try to disentangle it, and apparently, he succeeded, for his turn about over the shed was as smooth and steady as a trolley car coming around a curve. Then he sailed away toward the notth, every now and then describing a curve, first to the right, then to the left, and so on until be finally sank in the field for which he was aiming.

Another Airship Ahoy!

Meanwhile over the eastward the other machine had risen and came across the right angle to the course of the other, from the Stevens machine depended on a rope, which, he says, is 1,800 feet long, and which acts like the tail to a kite, steadying the flight. It has its disadvantages, for once it caught, some telegraph wires, and Stevens was prisoner until some lineman cut off a few feet of rope. Hi did his lofty circling, snooping in wide curves three quarters of mile in the air, while Mr. Boyce never got higher than 800 feet.

When Mr. Stevens began to descend his troubles began. He says a crank that controls the spark of his machine worked loose and began to fling out electric flashes so long that the aeronaut feared they would ignite the hydrogen, of which he had 22,000 feet in his gas bag. In reaching for this crank he knocked out a plug that controlled the machinery, and had to think of descending at once.

His long, trailing rope caught in the electric wires in front of Lundy’s fish market, Sheepshead Bay Road and First Street, and later his anchor, which he cast out, caught in these same wires ad there was a display of electric fire.

Stevens pulled the valves and came down on the electric light react and the wires , and half of the population of that part of the world came out and shouted to him that he would be grilled alive on those wires. He skipped about on the frame of his machine, however, until some lineman got a ladder up to him.

He freed his ropes, which were eagerly graped by as many of half a thousand volunteer assistants as could take hold, while he conducted the airship over the roofs to a large lot, where the descent was finally made in safety and comfort.

The race was a success from the standpoint of everybody but the trolley people, who are figuring what kind of an injunction will hold against these new birds of the air who mess up their wires with trail ropes and anchors.

Stevens’ anchor was pretty well burned by the electric wires.

Bonjour, sur la première photo montage, ce n'est pas le dirigeable N°4.. mais celui qui s'est posé sur le Champ de Mars..

ResponderExcluirSalut! Merci beaucoup pour votre participation :) - Oui c'est le No 4, le seul dirigeable de Dumont dans lequel il a remplacé le panier en osier par un cadre de vélo. Pour plus d'informations sur les inventions de S=D, je vous propose de visiter https://santosdumontlife.blogspot.com/2011/06/inventions-of-santosdumont-to-first.html

Excluir